League One scatter graphics - November 2024

Revisiting another classic visualisation

Subscribers and followers who are already familiar with my work pre-Substack will no doubt recognise these graphics, which are probably the ones I’m best known for.

For anyone who is seeing them for the first time, they are explained fully in this post but I will briefly recap some of that information here.

In a nutshell, there are four different graphics that compare different pairs of attacking and defensive numbers for all of the teams in the division.

Shot dominance

First of all, here is how the number of shots taken by each club compares with those they face in return. The average number of shots taken per match is on the horizontal and the average number faced is on the vertical, so bottom right (take plenty, allow few in return) is good while top left (take few, allow plenty) is bad.

The stripes are like contours: the greener the stripe, the better the performance (and vice versa for red). The matching labels that sit around the edges of the chart indicate how good (or bad) it is to be in each shaded area, based on the historical distribution of teams over previous seasons.

There’s an eerily clear divide in the league this season between teams who can muster 12+ shots per game and those whose average falls short of 11.

Shots aren’t telling the whole story however, as the likes of Wrexham, Lincoln and Mansfield are all challenging for promotion despite being in the latter camp.

The Stags are particularly interesting as they’ve allowed more shots per game than anyone else.

Meanwhile Rotherham are out-shooting their opponents overall yet find themselves in the bottom half of the table.

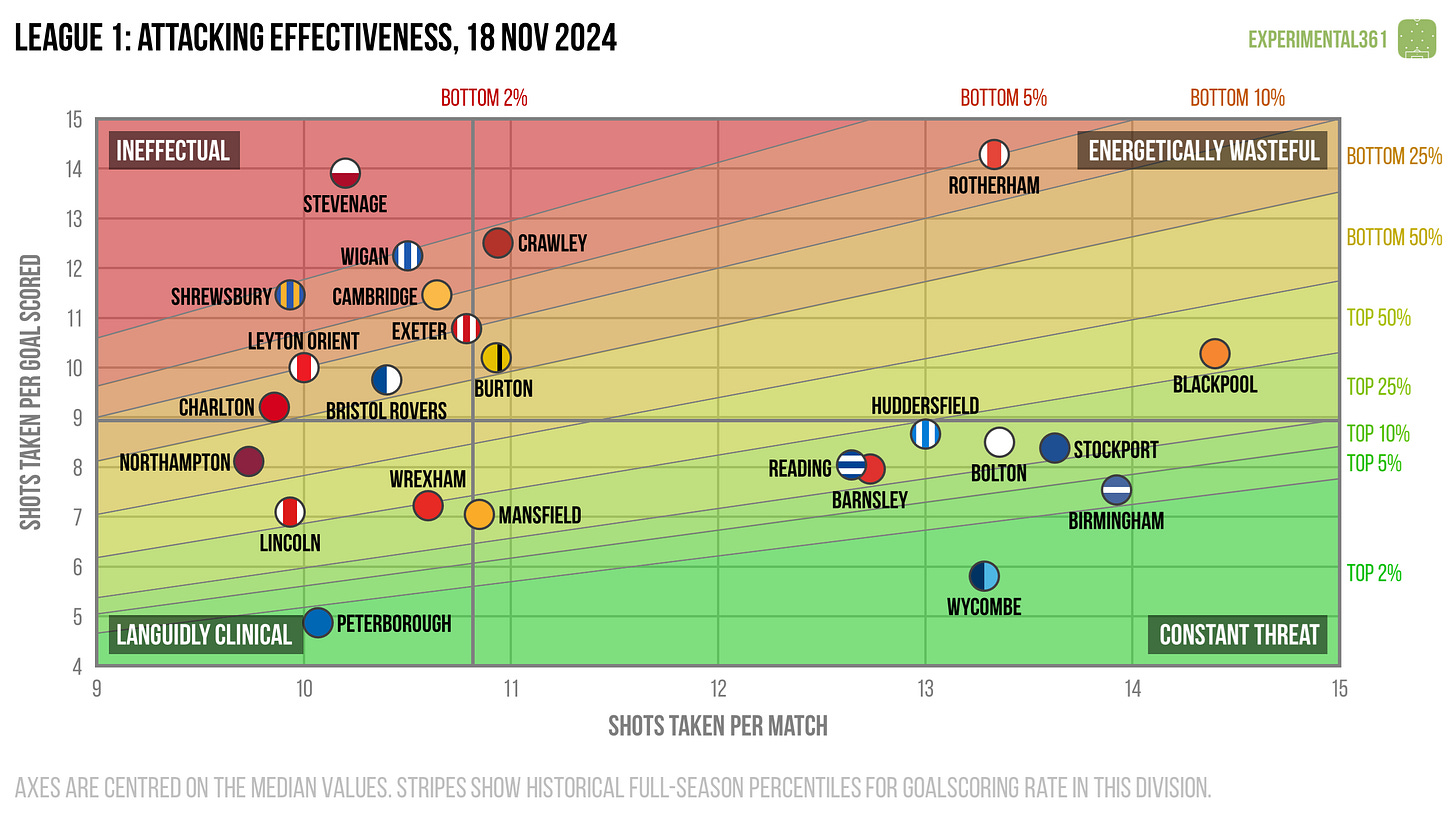

Attacking effectiveness

Now let’s look at attacking alone. The horizontal axis stays the same as in the graphic above, but now the vertical shows the average number of shots needed to score each league goal. Therefore bottom right is good (taking lots of shots and needing fewer efforts to convert) and top left is bad.

Rotherham’s malaise just got a bit easier to diagnose: they may not be struggling to create chances but converting them has been another matter entirely.

The aforementioned trio of Lincoln, Wrexham and Mansfield meanwhile have been turning shots into goals at twice the rate of the Millers, which has helped to keep them competitive.

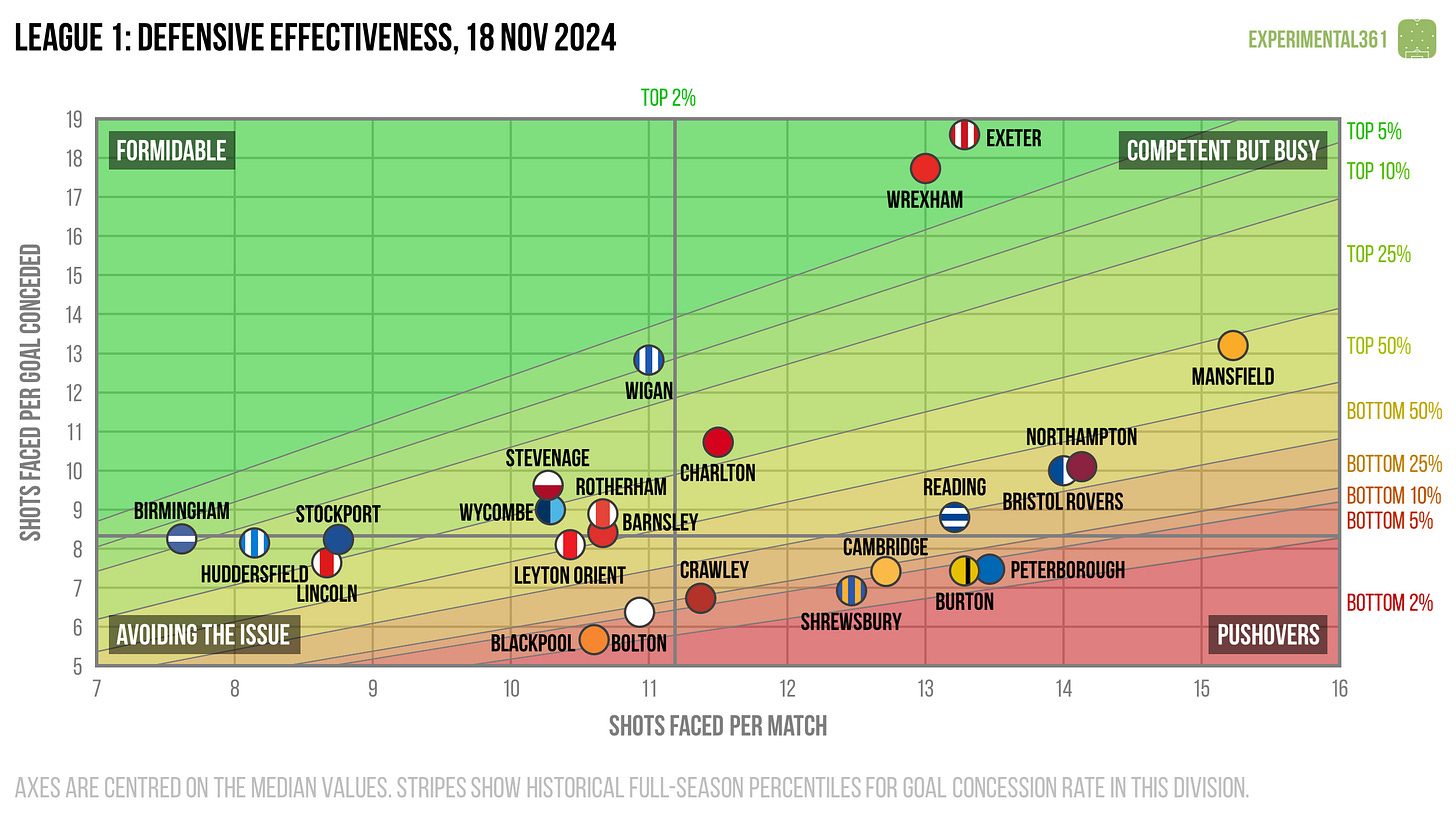

Defensive effectiveness

Next let’s look at the defensive situation – basically take the above chart and replace the word “taken” for “faced” on both axes. Now top left is good (facing fewer shots and soaking up more for each goal conceded) and bottom right is bad.

Exeter and Wrexham have let their opponents do plenty of shooting this season but have the best defensive records in the division. It remains to be seen whether their defences can maintain this level of resilience over a 46-game campaign, however.

Mansfield’s overworked rearguard is also doing a comfortably above-average job at keeping shots out of their net.

Expected goals

Finally here's a version of the first graphic that uses expected goals (xG) instead of shots, which should be a more accurate reflection of attacking and defensive quality. These are calculated using my own somewhat ancient model based on a relatively simple dataset, but in practice it tends to agree pretty well with the more advanced ones out there.

When we adjust for shot quality, there isn’t the same chasm in attacking output that we saw in the first chart.

For example, Peterborough are not taking very many shots (10.1 per game) but their average quality must be pretty high for them to be on a par with Reading (12.6 shots per game) here.

Newly-promoted Stockport have hit the ground running and are among the division’s top overall performers, giving two relegated teams (Birmingham and Huddersfield) a run for their money.

It will be interesting to see if Mansfield can sustain a play-off challenge as they are currently overachieving at both ends of the pitch.